WHEN DID EMPATHY BECOME A SIN?

Everyone counts. Kindness matters. Love wins. Simple principles many of us try to follow, right? Few people would consider them radical.

Until recently, that is.

It feels like something has shifted in our culture. Many days I feel bewildered and exhausted.

What about you?

Politically-charged animosities have fractured so many of our communities, neighborhoods and families. Even the prospect of trying to understand one another feels threatening.

It feels to me like our social fabric is at risk.

Also our long-held tradition of caring for one another. Cutbacks in humanitarian aid have already caused more than a half a million deaths, two thirds of whom are children. Think about Sudan, Ukraine or Gaza. Here, in the US, refugees and immigrants are not just being turned away at our borders, they are being hunted, dehumanized and incarcerated without due process. Kids are being separated from their parents.

All this makes me drop to my knees in prayer.

And that was before people started calling empathy a sin.

I’ve been calling empathy “a spiritual discipline” for the better part of a decade now — the only virtue muscular enough to meet the crucible we are living. Meanwhile, others are calling a empathy a sin and “the fundamental weakness of Western Civilization.”

The shock still leaves me numb.

Their argument goes something like this. Empathy is a trap because it’s too emotional, too manipulative. It is much better to sympathize, they say, feeling sorry but keeping a safe, unemotional distance.

Some Christians take it further by calling empathy “toxic” and “untethered” because it conflicts with biblical truth.

Really?

What is Empathy, Really?

There are two primary camps regarding empathy: some lead with the head and some lead with the heart. One group views empathy as primarily cognitive, the ability to know or understand how the other is thinking and feeling, similar to seeing their point of view. The other group views empathy as primarily affective, or emotional, the ability to feel what the other is thinking and feeling, almost like an emotional contagion. Each view has its own theories, supporters, and detractors.

Why not both?

To know her pain is to also know her joy. To feel her confusion is to recognize her clarity. Head and heart both. Why can’t empathy be thinking and feeling?

Brené Brown, one of my favs, defines empathy as the ability “to join others in their space, essentially telling them they are not alone—in joy or in suffering.” Roman Krznaric, a sociologist at Cambridge University, defines empathy as “the art of stepping imaginatively into the shoes of another person, understanding both their feelings and perspective, and using that understanding to guide your actions.” n order to connect with another person, we have to connect with something in ourselves that knows, at least in part, what she is both thinking and feeling.

Empathy is the state of “feeling into” another person’s reality, their level of emotions. But it’s also finding the place in ourselves where we connect with another’s perspective, their thought-space.

Taking Off the Gloves

Genuine empathy involves making a sacrifice for the sake of someone else, however large or small. But sacrifice always involves risk. This is where empathy gets controversial.

Blame it on Jesus.

Sometimes it’s tempting to sideline the humanity of Jesus—that he actually donned skin—in order to ruminate on his more divine aspects. Sometimes we forget that Jesus temporarily gave up his place beside God to take on the misery and helplessness of those he came to rescue. He came to us as a baby with a body and needs, born in blood and water. Jesus became human, one of us—approachable, understanding, listening, and ready to know and care about both our joy and suffering because he was there—fully human, fully aware, fully vulnerable, not distant or removed, but walking among us, giving his life away. The incarnation is the fullest expression of the empathy of God.

The word for empathy in the New Testament is splagchnizomai (yes, a mouthful!) which is usually translated “compassion” in the Bible. Jesus was “moved with compassion” when he was in crowds. (Mark 6:34; Matt 9:36; 14:14; 15:32). Compassion accompanied his miracles (Matthew 20:34) and his forgiveness (Matthew 18: 27).

So how did Jesus do with keeping that safe emotional distance?

Not so well.

Turns out splagchnizomai means “to have bowels of mercy” or “to love from the guts.” Hardly a distant, unemotional take, hey?

He didn’t stop there. In one of the most important parables in all of history, the Good Samaritan’s “love from his guts” that made him a hero. And not just love for anyone, but his sworn enemy.

Then Jesus essentially tells us to follow suit with the same kind of splagchnizomai as the Samaritan: “Go and do likewise” (Luke 10:33-37).

The Jews despised Samaritans so much they wouldn’t even say their name. Not in their worst nightmares would they expect the hero of the story to be the one they were trying to ignore, to un-see, to do away with.

Who are our Samaritans today? An immigrant? A refugee? A Muslim? A Democrat? A Republican? A Christian? An evangelical?

Seems like a bit of empathy could go a long way at bringing some healing to the world’s pain right now. I need it more than ever for the people I don’t understand, and even more for those I disagree with.

When it comes to empathy, I’m doubling down.

Join me?

If you need permission, dear friends, here you go:

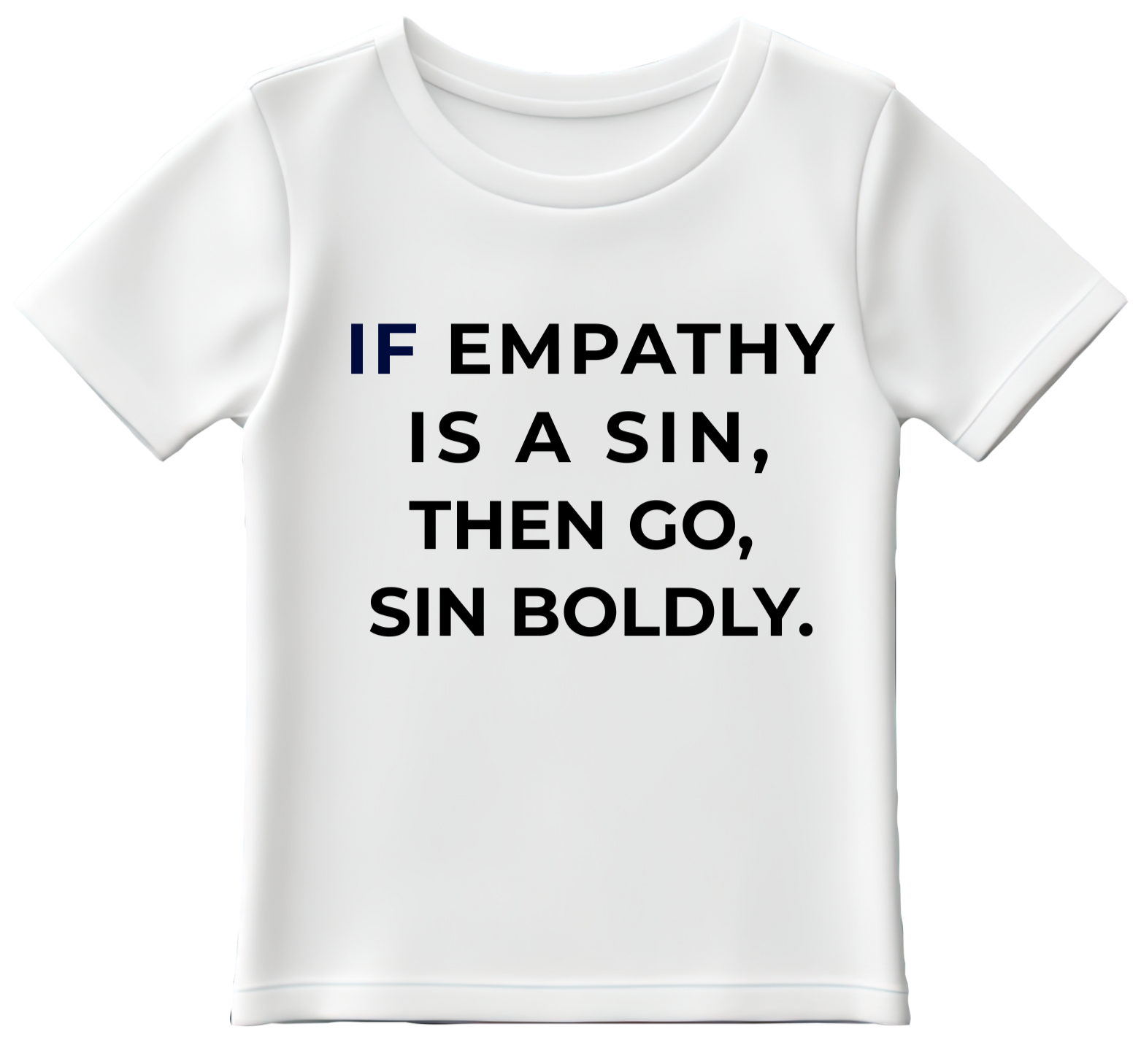

IF EMPATHY IS A SIN, THEN GO, SIN BOLDLY.

Stephan and I, and all of us at Together International, are cheering you on, dear friends.

Belinda

PS: I am working on the t-shirt :)